Now That We’re in a Recession . . .

Clifford F. Thies

- Clifford F. Thies is a professor of economics and finance at

Shenandoah University, in Winchester, VA. He can be reached at: cthies@su.edu.

Since 1854, the country has been through thirty-two business cycles. Periods of expansion have averaged about five years, and periods of recession about one-and-a-half years. Moreover, since the 1930s, recessions have been relatively short, averaging less than twelve months.

As it takes some time to say for sure that we are in recession, by the time

we know we are in recession, we are already most of the way through it. This

time, it took eight months, from March until November 2001, to determine

we were in a recession. Here we are in [February 2002], and there already

are some signs that we may soon start to recover.

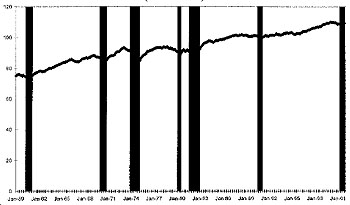

| Fig. 1. Conference Board Index of Coincident Indicators (1996 = 100) |

|

Overall, business cycles are marked by an index (or average) of four

broad measures of economic activity—Sales, Income, Production and

Employment. According to the Index of Coincident Indicators com-piled

by the Conference Board, shown in Figure 1, the economy started leveling off in late [2000]. In November 2001, the committee of six

economists of the National Bureau of Economic Research that “calls”

the turning points of the business cycle, determined that the economy

fell into recession in March 2001.

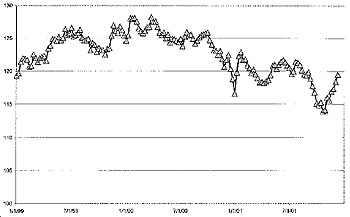

Along with its Index of Coincident Indicators, the Conference Board

compiles an Index of Leading Indicators and an Index of Lagging

Indicators. The leading indicators include measures of new orders for

durable goods and permits for housing construction, along with finan-cial

variables such as the money supply, the stock market, and certain

interest rates. The leading indicators might be interpreted as measures of

business and consumer plans and expectations. As is clear in Figure 2,

the Index of Leading Indicators turned down in late 2000, signaling a

slowdown of the economy.

| Fig. 2. Conference Board Index of Leading Indicators (1996 = 100) |

|

While subtle, it appears that the Index of Leading Indicators turned back

up early during 2001. It might have been that, without the September 11th

attack on our country, the economy would already be in recovery, and might

not have officially fallen into recession. However, with the attack, an

already weak economy was moved into recession status.

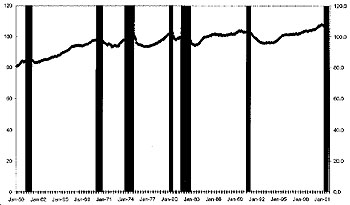

Thus far, only two month’s data have been tabulated by the Conference

Board following the September 11th attack, a fall, followed by an uptick. A

leading indicator series consisting of a smaller number of components

observed on a weekly basis is available nowadays from the Economic Cycle

Research Institute. To be sure, this series is subject to a lot of variation.

Nevertheless, the series seems to indicate that the economy faltered and then

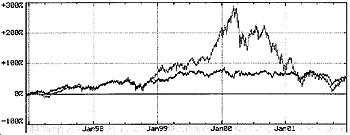

subsequently recovered following the September 11th attack (see Figure 3).

| Fig. 3. ECRI Weekly Index of Leading Indicators |

|

As was already mentioned, the Conference Board compiles an Index of

Lagging Indicators. The lagging indicators include measures of the dura-tion

of unemployment, business inventories, and commercial and consumer

indebtedness. The lagging indicators can be interpreted as measures of the

degree to which the plans of businesses and consumers go unfulfilled.

Unemployment, for example, is the plan of someone to find a job that

did not match up with the plan of someone else to hire. And, inventory is the

plan of someone to sell that did not match up with the plan of someone else

to buy.

A market economy is, by definition, a decentralized economy. This

means that all of us, in our capacities as buyers and sellers, employees and

employers, borrowers and lenders, and so forth, make plans that depend, for

their fulfillment, on the plans of others. Usually, these plans are coordi-nated,

well enough, by the adjustment of prices, bringing supplies and

demands across many different markets into balance. But, sometimes, there

is a breakdown of this coordination process. Supplies and demands do not

match up very well, at least not for a time.

Often recessions involve false signals, such as artificially low interest

rates due to expansionary monetary policy, or an abrupt change, such as the

start of a war. In such cases, businesses and consumers are often caught in

the middle of their plans, and are only able to make changes at considerable

cost. Thus, the lagging indicators often involve distress, such as unem-ployed

workers, businesses stuck with unsold inventories, and borrowers

dealing with burdensome debt.

| Fig. 4. Conference Board Index of Lagging Indicators (1996 = 100) |

|

What is interesting about the Conference Board Index of Lagging

Indicators is that it seems very sensitive, nowadays, to the business

cycle. The relatively mild recession from July 1990 to February 1991

was followed by a substantial fall in the lagging indicators (see Figure

4). This means that people were dealing with distress for some time

following the start of recovery.

Perhaps you remember when President George Bush (the First) was

asked, during his reelection campaign, if the economy was in recession.

He answered that the economists were not sure. That may have been the

scientifically correct answer, but it was not the politicallycorrect an-swer.

He should have replied, “It doesn’t matter what the economists

say. People are hurting.”

The same thing can be said today. We may be seeing the first signs

of recovery, but the distress associated with the recession will probably

continue to get worse for some time.

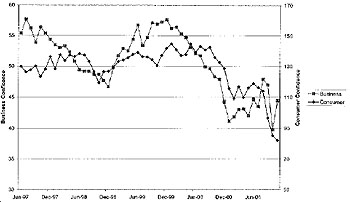

Consumer Confidence

A number of commentators are focused on the issue of “confidence,”

especially consumer confidence. They seem to think that we can borrow and

spend our way out of this recession. To be sure, the Conference Board

includes a measure of consumer confidence in its Index of Leading Indica-tors.

While consumer confidence leads the coincident indicators, it seems

to follow, rather than coincide with recent news about the economy.

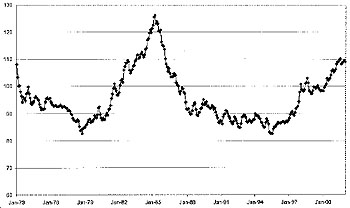

| Fig. 5. Consumer Confidence (from Conference Board survey) and Business Confidence (from Nartl Assn of Purchasing Managers survey) |

|

In Figure 5, I have juxtaposed an index of consumer confidence

(constructed from several answers to a monthly survey of consumers

conducted by the Conference Board) against an index of business

confidence (constructed from several answers to a monthly survey of

purchasing managers). Both series started to fall prior to the recession

that began in March 2001. However, it is clear that business confidence

started to fall first.

It is also clear that business confidence started to pick up, as it should

have, along with the aborted recovery of the economy prior to the Septem-ber

11th attack. Consumer confidence merely stopped falling. Both busi-ness

and consumer confidence fell precipitously upon the September 11th

attack; however, business confidence rebounded in the subsequent monthly

survey, while consumer confidence continued to fall a little.

The greater timeliness of business confidence than consumer confi-dence

should not be surprising. Businessmen, and purchasing managers in

particular, are naturally more focused on the economy, whereas most

consumers merely filter what is already in the news and what developments

they may be aware among themselves and their family and friends.

The cause of the recession, however, was not consumer spending, as the

American consumer had been spending like a sailor on shore leave (until the

September 11th attack). The problem was, to quote Alan Greenspan,

“irrational exuberance” in the stock market. The problem manifested itself

in at least two ways: a dollar that was so strong in the foreign exchange

markets as to cause American producers—including farmers and manufac-turers—

to lose competitiveness, and the "debt-capitalization" of certain corporations at artificially high valuations, putting them at the risk of

bankruptcy upon a stock market correction.

The Cause of the Recession of 2001

In addition to turning our attention to recovery, the official designation

of the recession allows us to argue over what caused it. In this case, the cause

is pretty obvious. At least, it’s pretty clear to me.

| Fig. 6. Accumulated Returns of Dow-Jones and Nasdaq Indices. |

|

In Figure 6, I have graphed the accumulated returns on the Dow Jones

Industrial Average, an index of thirty well-established companies spread

across the major sectors of the economy (the smoother line) and the Nasdaq

index, an average of the thousands of companies, including many compa-nies

in the “infotech” sector, that trade in the Nasdaq market (the spiked

line). (I constructed the chart in Yahoo.) It’s pretty obvious, looking back,

that going into 1999 a speculative bubble got underway, and then, during

2000, that the bubble burst.

During times of speculative bubbles, stock prices are driven by the

“greater fool” theory. Normally, investors are guided by the rule of “buy

low, sell high,” meaning buy securities that are underpriced relative to their

underlying value, and sell those that are overpriced. This rule keeps stock

prices about their underlying values. But, during speculative bubbles,

investors are guided by the rule “buy high, sell higher,” on the theory that

there is a “greater fool.”

In early 2000, sensing that the air was getting thin, I moved about

half of my portfolio out of equities and into money market securities. I

knew I was going to regret that decision. If the stock market went down,

which it did, I’d regret moving only half of my portfolio. If, contrari-wise,

the stock market went up, I’d regret moving the half that I did.

Either way, I was going to kick myself.

On the other hand, if I had just kept my money in the stock market

during the past five years, ignoring the ups and downs, Figure 6 shows

that I would have made a return of forty-five percent (this does not

include the dividends I would have received). For most investors, thebest advice is indeed to ignore the ups and downs of the market, and

simply invest in stocks for the long-term.

Speculative bubbles pose certain problems for the economy. During the

past few years, in large part because of our strong stock market, the U.S.

Dollar has gotten very strong in the foreign exchange market. In the long-run,

the exchange rate of any currency will tend to reflect its purchasing

| Fig. 7. Real Exchange Rate, US $ versus “Market Basket” of Foreign Currencies (source: U.S. Treasury) |

|

power. That is, in the long-run, the goods and services that you can buy with

$100 here in the United States will approximately equal what you would be

able to buy, for example, in England, having exchanged the American

money for British pounds. But, this is only a long-run tendency. From time

to time, currencies deviate from purchasing power.

During the last few years, as during the years from about 1981 to about

1985, the dollar has gotten very strong in the foreign exchange markets of

the world, much more than purchasing power would dictate (see Figure 7).

The main reason has been the strength of the U.S. securities markets.

Investors all around the world see U.S. securities as both among the most

secure and the highest yielding. But, in order to “buy into” the American

securities markets, they first have to buy dollars. The “raging bull” stock

market of the past few years, just like the bull market associated with Ronald

Reagan’s first term, has resulted in a strong demand for the dollar and a

dollar that is overpriced in terms of other currencies.

The overly strong dollar has been bad news for the many American

farmers and manufacturers. Farmers involved in commodity crops such as grains, and the apple growers of this part of Virginia, have lost competitive-ness

in world markets. This applies both to exports and to competing against

imported farm products.

In 1985, following a meeting at the Plaza Hotel in New York, the

finance ministers and central bankers of the major economic nations of the

world announced that they considered the dollar to be overpriced. The dollar

quickly fell to a level more consistent with purchasing power. During the

past few years, a series of financial crises in the world may have impeded

similar action. And, now, we are focused on the Afghanistan War. Never-theless,

it would be good it a similar corrective could be arranged.

A second, and somewhat more complicated, way that the stock market

bubble of the past few years has disrupted our economy is that a number of

companies re-capitalized themselves at the peak of the market. They

assumed debt obligations that looked reasonable at the time, but which have

proven burdensome following the stock market correction. In theory, this

problem could be quickly resolved by a ruthless application of the priority

of claim of the security holders involved, with minimum impact on the

economy. However, our legal system allows a lot of room for debtors-in-default

to forestall judgment, during which time the workers and assets of

their firms are at risk.

In conclusion, there’s good news in the admitting we are in a recession.

Instead of asking questions such as Are we in? or When will we fall into

recession? we can now turn our attention to Are we in? or When will we be

in recovery?

[ Who We Are | Authors | Archive | Subscribtion | Search | Contact Us ]

© Copyright St.Croix Review 2002