had earned degrees from Butler University and Columbia University — the latter a Ph.D. in philosophy — and had served several churches as a minister, before he accepted a position as the pastor of People’s Congregational Church in Bayport, Minnesota. My family were not members of that church, but came to know Angus when he brought the first issue of his journal, then called Religion and Society, to my father’s printing plant which was delivered (comprising 32 pages plus covers) on January 3, 1968, and billed at a total cost of $252.55.

Back at that time, the contents of the publication were set up in metal type and printed by letterpress, much as printing had been done for the preceding 500 years. Reflecting on the technology we used to print those journals, I’m reminded of how greatly life has changed in the past four decades. Not only those old methods, but also much else that then seemed just as settled and solidly established, are now “one with Nineveh and Tyre.” Some of the changes have been for the good, and others have not been. What Angus made his life’s work at The St. Croix Review has to be considered in light of the condition in which religion and society — his great concerns — stood back then in 1968. With the rapid economic growth that followed World War II, and the prosperity it brought, also had come serious social unrest. The Vietnam War was at its height, race riots marred the order of our cities, and Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” programs had just been enacted, putting in place the modern welfare state which has burgeoned so expensively since then.

Today, when we hear anything about the involvement of religion with politics, it is usually in connection with the so-called religious right. That was not so in the 1960s. The “social gospel” movement was at its apogee amongst the mainstream Protestant denominations and had strong adherence amongst Roman Catholics as well. It basically jettisoned the traditional concerns of Christianity with personal virtues and the transcendent aspects of religion, substituting in their stead a program of social change and reorganization. Nationally prominent religious leaders of the day included such anti-war figures as the Rev. William Sloane Coffin, the Quaker Staughton Lynd, Fathers Phillip and Daniel Berrigan, as well as civil rights organizers such as the Reverends Martin Luther King, Ralph Abernathy, and Adam Clayton Powell. These members of the “religious left” unapologetically made common cause with atheistic Communism. Staughton Lynd, for example, visited Hanoi, while Martin Luther King, who recently has been portrayed as a sort of secular saint, did not scruple to associate with known Communists such as Stanley Levison and Hunter Pitts O’Dell.

Sometimes immigrants — as Angus was — appreciate America and its heritage better than the native-born do. Angus valued the American way of life, and was proud to be an American citizen. He knew the value of American freedom and opportunity, which those of us who have lived all our lives here so often take for granted. And he rejected the viewpoint of the 1960s religious left, not only because it set historic American principles at naught (or less), but also because he understood that one cannot have a decent and honorable society without decent and honorable individuals. In abandoning, even rejecting, the cultivation of personal virtues, the religious left had abandoned the sine qua non of the good society. In this, it made the mistake that materialists always do, and which we have seen in one failed socialist country after another. As Andrei Navrozov observed, the Soviet Union tried for seven decades to create New Socialist Man, and the result was only to produce a race of proficient thieves.

It was personal virtue that Angus held paramount, in his own life and in that of others. One of Angus’s most characteristic moments was a time when an acquaintance wished to dispute some abstruse point of theology with him. Angus could easily have done it, with his great store of academic knowledge; but instead, he said to this person, “Don’t tell me what you believe — I’ll watch how you behave, and I’ll tell you what you believe.” The University of Chicago scholar Richard Weaver wrote a book many years ago, entitled Ideas Have Consequences. This book title has become a sort of slogan amongst conservatives, many of whom have never read the book. Angus would have said that ideas that don’t have consequences are just idle chatter — and he was impatient with idle chatter. Of course, many ideas have had bad consequences, and it’s important to know what these are; but our efforts should be focused on those ideas that have good consequences, and on achieving those good consequences. Translating right belief into right behavior is always a challenge, and it was explaining and exemplifying this to which Angus devoted his life.

We are still in the midst of Christmas’s twelve days, and Christmas is above all the season of giving. The best gifts we receive are those that we didn’t expect, and probably didn’t deserve. That’s the way God’s grace works, and God’s grace is after all the point of the holiday. I can only conclude by saying that it was certainly by such grace that I enjoyed the good fortune to have known Angus, and that all his friends and his readers did. Today, we say a regretful farewell to this wise and good man — tomorrow, and in the future, let us honor his memory by continuing his work. *

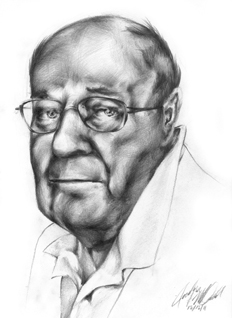

Angus MacDonald had already lived more than half of his long and remarkable life by the time I became acquainted with him. He had been born and grown up in Australia, had been ordained a clergyman, had emigrated to the United States on the first ship to carry civilian passengers to this country after World War II,

Angus MacDonald had already lived more than half of his long and remarkable life by the time I became acquainted with him. He had been born and grown up in Australia, had been ordained a clergyman, had emigrated to the United States on the first ship to carry civilian passengers to this country after World War II,